5. Ice in the Arctic

Measuring sea ice

Drilling to measure ice thickness.

Source: Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research

What do we need to know about sea ice?

- The area it covers - extent

- Thickness

- Volume

- Age

- Concentration

and, very importantly, how all these vary with time and location.

If we are looking at the amount of solar radiation reflected away by sea ice, the albedo, then the total area or extent of ice coverage may be the most important quantity for us to measure.

Alternatively if we are studying how mammals are affected by changes in sea ice, then local cover and thickness may be the key quantities.

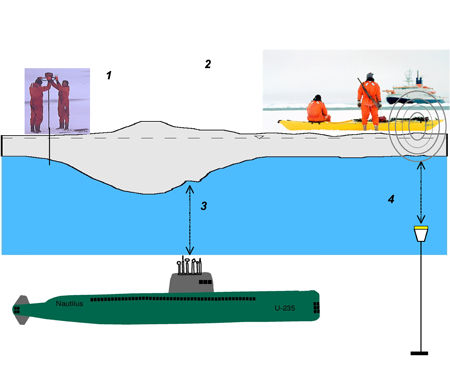

Measurements of sea ice can be made from above, by satellite and aircraft, from below by submarines and other underwater vehicles, on the surface, and from boats, buoys and moorings.

Sea ice extent from satellite

Satellite sensors have provided measurements of sea ice extent since 1979. They allow us to view almost the whole area covered by sea ice, on a daily basis. You will fin some references to such data on the internet on page Links.

Different sensors provide different types of information:

MODIS and MERIS are examples of instruments operating in visible wavelengths. Ice has a high reflectance and so appears bright in visible images

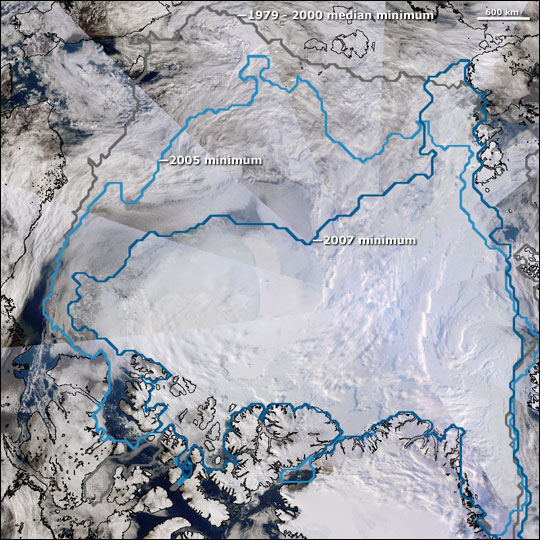

The 2007 minimum, which correlates closely with the ice visible through clouds in this image, fell substantially below previous records.

Source: National Snow and Ice Data Center

Seeing through cloud and at night

Much of the Arctic is either cloudy or in darkness for long periods of time. Because of this satellite sensors that rely on reflected sunlight or emitted infrared radiation will not give us a complete picture of the ice. The image mosaic above was obtained during relatively cloud-free conditions during the Arctic summer.

Year-round satellite monitoring of ice cover relies on microwave sensors. Passive microwave sensors have provided 30 years of sea ice data.

We mainly use microwave sensors to monitor sea ice. This is because these sensors 'see' through cloud and do not rely on daylight.

Passive microwave instruments

Examples of passive microwave sensors are the Special Sensor Microwave/Imager (SSM/I) and the Advanced Microwave Scanning Radiometer-EOS (AMSR-E).

Passive microwave sensors detect radiation emitted by the surface. They provide information on the temperature of the surface, its roughness and the salt and liquid water content. Their main drawback is that they have a low spatial resolution.

Active microwaves

Radars are active sensors - they measure the return from the surface of a signal sent by the sensor. Spatial resolution and coverage depend on the type of radar, with resolution of 10 or 20 metres for the synthetic aperture radar (SAR).

Satellite radars

Examples of satellite radars used for sea ice studies include Quikscat (scatterometer), Radarsat (SAR) and the radar altimeter on ENVISAT.

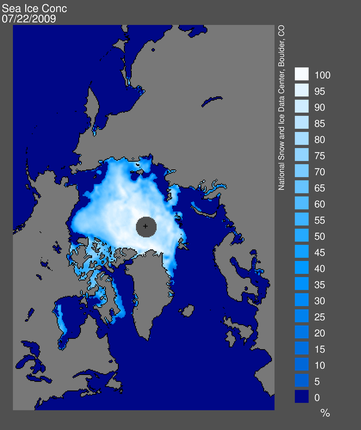

Sea ice Concentration

Concentration describes the relative amount of area covered by ice, compared to some reference area. Ice concentration typically is reported as a percentage (0 to 100 percent ice), a fraction from 0 to 1, or sometimes in tenths (0/10 to 10/10). A value of 0 means there is no ice, while a value of 100 means the region is completely covered by ice.

Source: National Snow and Ice Data Center

Ice concentration affects both human activities and biological habitats. For example shipping may be able to negotiate areas of low ice concentration whilst arctic mammals which hunt, breed and feed on sea ice will prefer higher concentrations.

Measuring sea ice thickness from the surface (and below)

Source: Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research

Sea ice thickness from satellite

Satellites can measure sea ice height above the water surface. This measurement known as 'freeboard' can be related to total ice thickness. Radar altimeters and the Lidar on ICESat can measure freeboard.

These measurements rely on there being some open water such as in leads, polynyas. See supplement 5 for more about ICESat and ice thickness.

Volume

The total volume of sea ice is obtained by combining measurements of sea ice area and thickness. Satellite data for the arctic from the last thirty years is available, but ice thickness for the whole of the area, based on freeboard data, from satellites, is only available for the past few years. Other measurements of ice thickness from the surface only cover a small geographical part of the Arctic.

Age

Ice age can be estimated from satellite data because age affects the way ice is seen in different parts of the electromagnetic spectrum. For example both surface roughness and the amount of salt present in the ice depend on the age of the ice, and can affect microwave data.

Want to know more about satellite measurements of sea ice?

See supplement 3

A closer look at a satellite image of sea ice in the exercise