5. Ice in the Arctic

Facts and figures

Growing and melting

Sea ice starts to grow during the autumn as air temperatures fall below the freezing point of sea water. The ice becomes thicker during the winter and then begins to melt as temperatures rise again in spring and summer.

In some areas all the ice will melt, but where it is thick enough, it will just thin and then thicken again the following autumn. So some sea ice may remain for several years, thinning during the summer and regrowing the following autumn and winter.

Some of the properties of sea ice depend on how old the ice is, so it is important to distinguish between the different ages of sea ice.

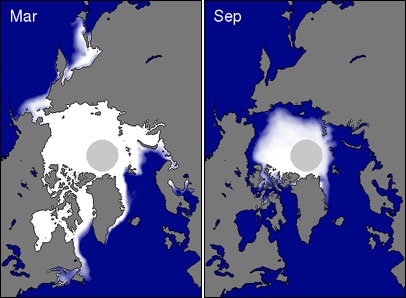

Arctic sea ice typically covers about 14 to 16 million square kilometres in late winter. By the end of summer, sea ice only covers approximately seven million square kilometres (and only 4 - 6 million in recent years).

About 15 percent of the world's oceans are covered by sea ice during part of the year.

Slow freezing

We know that when fresh water at temperatures below 4°C (where it has a density maximum) cools to near its freezing point, its density decreases. Ice has a density which is 9% less than liquid water at the freezing point - this is why ice cubes float in a jug of water. What about salt water?

As the surface temperature drops in autumn, the salt in ocean water causes the density of the water to increase as it nears the freezing point; there is no density maximum at 4°C. So as soon as the surface water gets really cold it starts to sink, until the surface water reaches the freezing point and freezing takes place.

As a result, sea ice forms slowly, compared to ice in freshwater, because salt water sinks away from the cold surface before it cools enough to freeze.

Due to wind and waves there is always a strong mixing of water in the upper water column. Therefore, the top 100 to 150 metres of water must be cooled to its freezing point for sea ice to form.

Where does the salt go?

As frazil ice crystals form, salt accumulates into droplets called brine, which are typically expelled back into the ocean. This raises the salinity of the near-surface water. Some brine droplets become trapped in pockets between the ice crystals. These droplets are saline, whereas the ice around them is not.

The brine remains in a liquid state because much cooler temperatures would be required for it to freeze. At this stage, the sea ice has a high salt content. Over time, the brine drains out, leaving air pockets, and the salinity of the sea ice decreases.

Source: US National Snow and Ice Data Center

Defining the age of ice

New ice is less than 10 centimetres thick formed this season.

Young ice is 10 to 30 centimetres thick. Young ice is sometimes split into two subcategories, based on colour: grey ice (10 to 15 centimetres) and grey-white ice (15 to 30 centimetres).

First-year ice is thicker than 30 centimetres, but has not survived a summer melt season.

Multiyear ice has survived a summer melt season and is much thicker than younger ice, typically ranging from 2 to 4 metres thick. Multiyear ice contains much less brine and more air pockets than first-year ice. Less brine means "stiffer" ice that is more difficult for icebreakers to navigate and clear.

Multiyear ice often supplies the fresh water needed for polar expeditions.

More on ice ages and growth/melt on the next page