6. Currents from Space

Global measurements?

The large oceanic currents are the result of wind forcing and variations in water density.

A drifter dropped in such a current can measure how fast it is going by timing its motion. In addition to drifters, there are other specific instruments to measure currents called currentmeters and ADCPs (acoustic doppler current profilers) – the latter work by emitting a sound and measuring the echoes reflected by the moving particles in the water.

Insufficient data?

But these point-wise measurements don't cover all the oceans. You need the instrument, the drifter or the ship actually to be there, in the place where you want the current to be measured. And the oceans are huge – 71% of the earth surface – with many areas remote and inhospitable, such as much of the Southern Ocean.

Argo floats can help to some extent – but their present fleet of 3,000 floats still leaves gaps, and as they are passively transported by currents they cannot be directed where one would like to make the measurements.

You may think that getting an accurate picture, like a ‘snapshot’ of the currents over the entire globe, is virtually impossible.

Think again!

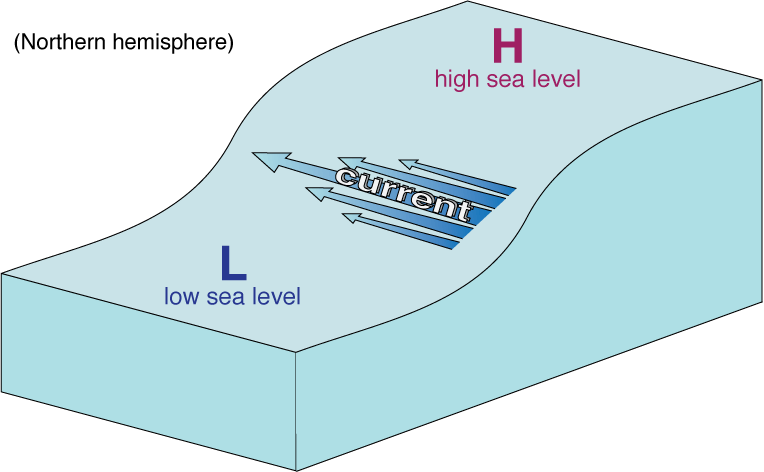

Oceanographers have long known that currents at the sea surface have an impact on the elevation of the sea surface itself. They cause bumps (hills) and troughs (valleys) on the sea surface, variations of level that would simply not be there if the water were still (not flowing).

Not as flat as you might think!

In other words, the sea surface under the effect of currents is no longer perfectly horizontal – it has an almost imperceptible slope (tilt). The stronger the current, the greater the tilt: therefore, if we can measure the tilt we can estimate the surface current.

Too small too see?

But do not think that you will be able to see the surface tilt with your naked eye! Even for the stronger oceanic currents it is normally not more than 2 cm of height variation over 1 km in distance. And the overall ‘jump’ between the two sides of major currents such as the Gulf stream or the Kuroshio is only a couple of metres over a few hundred kilometres.

The great thing is that these slight variations in sea level are successfully seen from space – by an instrument known as a radar altimeter.