4. The Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem (BCLME)

A highly productive coastal upwelling system

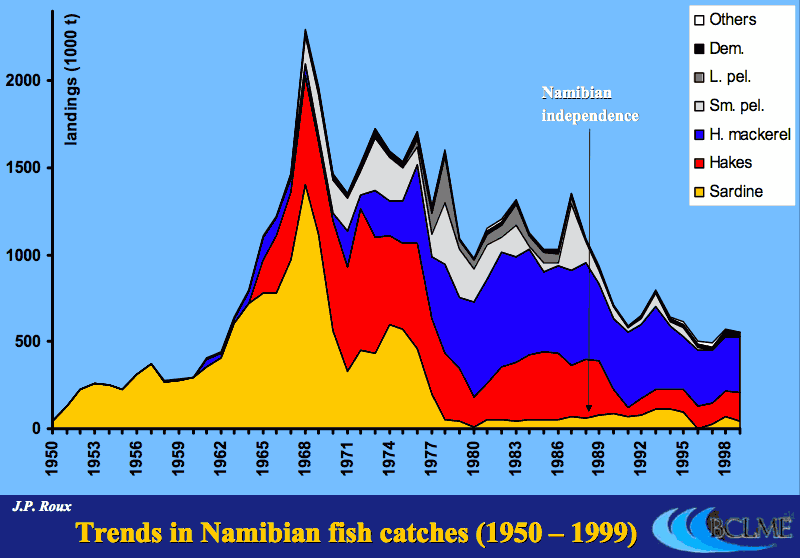

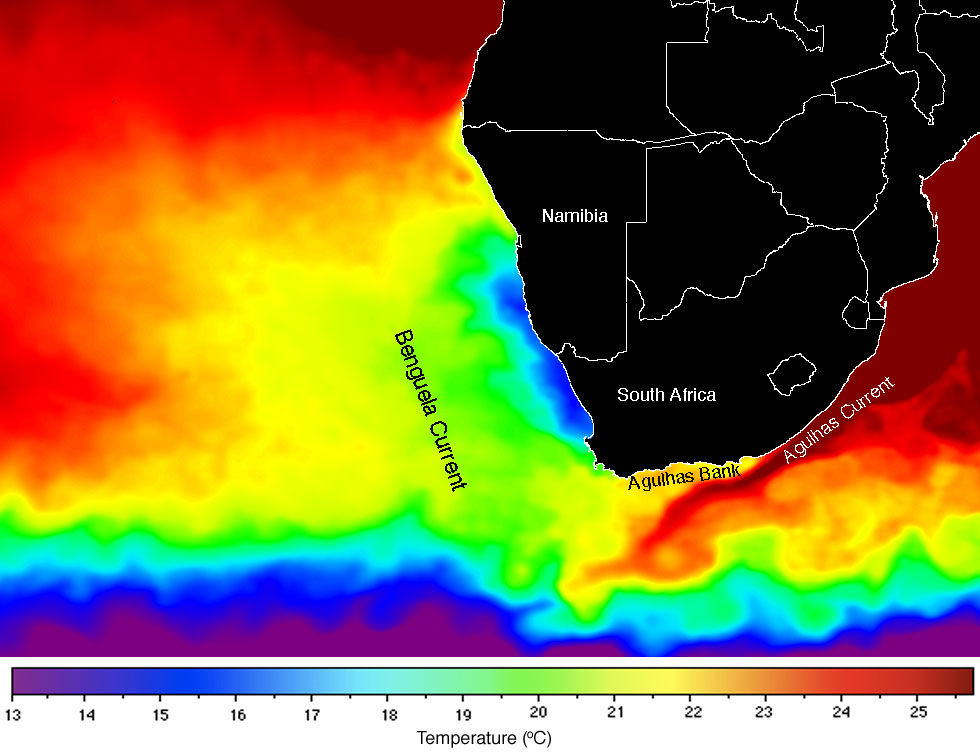

The Beguela Current LME is the strongest coastal upwelling system in the world. It is highly productive and supports a rich fishery with catches of rock lobster, cods, hakes and haddock, sardines and anchovies of over a million tons per year.

Sardines and anchovies spawn on the Agulhas Bank, and their eggs and larvae drift with the westward current back into the Benguela system.

These small fishes are a rich source of food for larger fish species, marine mammals and birds. Sardine and anchovy are commercially important, but have declined in recent years.

Over-fishing, habitat modification through coastal development, and a high pollution risk associated with ongoing seabed mining and off-shore oil productiona are all potential threats to the ecosystem, unless they are carefully managed.

International collaboration

The Benguela Current ecosystem stretches from the tip of southern Africa to the front with the Guinea current off northern Angola.

To meet the challenges of sustainable management of the Benguela system, South Africa, Namibia and Angloa have joined in the Benguela Commission to deal with environ-mental issues that cross national boundaries. See Links

Transboundary issues include the migration of valuable fish stocks across national boundaries, the introduction of invasive alien species via the ballast water of ships moving through the region, and pollutants or harmful algal blooms that can drift with winds and currents from the waters of one country into another.

The countries collaborate to

- develop fishery regulations based on sound knowledge of the ecosystem,

- develop a viable mariculture policy,

- analyze the socioeconomic consequences of different harvesting methods,

- solve conflicts between fisheries and coastal and offshore diamond, gold, oil and gas production.

Harmful algal blooms and sulphur eruptions

High phytoplankton productivity in the nutrient rich upwelling waters is the basis for the rich life in the Benguela. But the favourable conditions can also lead to harmful algal blooms. The blooms occur naturally as a result of the high nutrient content in the upwelling water, but pollution from sewage and land run-off may increase the risk.

When a dense bloom is over, the phytoplankton die and sink. As they decompose they use all the oxygen in the water. Bottom dwelling animals suffocate if they cannot escape.

The lack of oxygen in sediments under the strongest upwelling areas means that decomposition often produces hydrogen sulphide (which is toxic and smells like rotten eggs), and colours the sediments black.

Sometimes the sulphurous gases escape from the sediment and rise towards the sea surface in huge eruptions that are visible from space (left). These toxic eruptions can kill billions of fish. See Links

Concerns about global warming

Both the harmful blooms and the sulphur eruptions may increase with global warming. There is also concern that global warming may disrupt the balance of upwelling, sheltered areas and mixing between warm and cold currents that is so favorable to the anchovies and sardines.

Periodic El Niño like events already cause disruption of fish, bird and mammal migrations, and seriously reduce fishery recruitment. These ‘Benguela Niños’ may become more frequent as the world warms.