The Roaring Forties and the Antarctic Circumpolar Current

Is there a 'right' way to sail around the world?

If you listen to sailors, there is certainly a wrong way: from east to west, against the wind and currents.

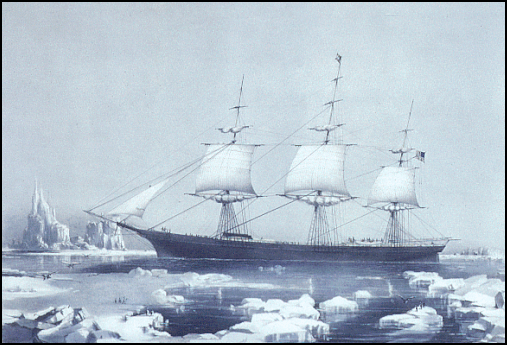

In the old days of wind power, before the Panama Canal, ships had to round Cape Horn on the southern tip of the American continent to move people from the Atlantic side of America to the Pacific west coast. Cape Horn was notorious for its hazards: strong winds, large waves, and icebergs drifting up from Antarctica. Whoever had rounded the Cape westward belonged to a superior class of men; they could carry an earring on their left ear, and urinate into the wind.

It's much the same today. Sailing around the world means braving the Southern Ocean, the cold, stormy, ice-berg ridden seas around Antarctica. Doing it the wrong way, westward against the wind, just adds to the challenge.

The Roaring Forties

Rounding Cape Horn westwards means sailing against the Roaring Forties - the prevailing westerly winds that circle the world between 40 and 60 degrees South. There is no land to break the wind, so the Roaring Forties are stronger and more persistent than the corresponding westerlies in the northern hemisphere. The average wind speed between 40°S and 60°S is 15-24 knots (8-12 m s-1), with strongest winds typically between 45°S and 55°S.

The Antarctic Circumpolar Current

The Roaring Forties drive the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC). This is the greast current in the world, with a flow equal to more than a hundred times that of all the world's rivers put together. Yet along most of its course the current speed is only about 20 cm s-1 or less.

The huge volumes of water transported by the ACC is not due to its speed, but to its width and depth. Unlike other wind driven currents, which generally extend no deeper than 800-1000m, the ACC from the sea surface to depths of 2000-4000 m, and can be as wide as 2000 km.