1. How Currents Affect Us (4/4)

Currents influence regional climate

Summer at Mawson, Antarctica, 67°S. Photo: Ray Hegarty

Summer at Mawson, Antarctica, 67°S. Photo: Ray Hegarty

Why so different?

On the right are summer photos from three different places, each at about 70 degrees latitude.

Over the period of a year each place receives about the same amount of solar energy at the top of the atmosphere. Despite this they have very different climates.

How would you explain the differences?

The importance of water

The role of the ocean in our climate is closely linked to the remarkable heat capacity of water.

Because the latent and specific heat of water are both so high, the movement of water through the Earth system also moves large amounts of energy.

Maritime climates

The high heat capacity of the ocean acts as buffer to sharp changes in temperature. This is why maritime climates have lower maximum and higher minimum temperatures than inland climates.

Water vapour is a strong greenhouse gas, so the high humidity of sea air also acts as a blanket to keep heat from radiating out to space at night.

Warm currents release energy into the air, both directly and as heat contained in water vapour. As a result, land down-wind of warm currents such as the Gulf stream are warmer and wetter than countries at similar latitudes elsewhere.

At mid-latitudes the effect is most noticeable in winter. The current releases heat and moisture to the atmosphere, bringing fog or drizzle when the warm sea air cools down over land.

Tropical and subtropical countries bordering warm currents usually have hot, humid climates. Prevailing on-shore winds bring storm systems powered by the high content of water vapour, with heavy rainfall and high risk of flooding.

Countries next to cold currents, on the other hand, generally have cooler, drier climates.

During warm periods fogs are caused by hot air from land cooling down as it flows out over the much colder sea. Such fogs are the main source of moisture in the coastal Namib Desert of Southern Africa, next to the cold Benguela Current.

Summer at 70 degrees latitude

Summer in Scoresbysund, Greenland, 70°N. Source:

Georg Gollman

Summer in Scoresbysund, Greenland, 70°N. Source:

Georg Gollman

Summer on Vanna, Norway, 70°N. Source: blackone

Summer on Vanna, Norway, 70°N. Source: blackone

Seasonal weather predictions

It is generally not possible to forecast the weather more than a few days in advance, but useful predictions of average conditions can be made a few months ahead, based on information about the ocean.

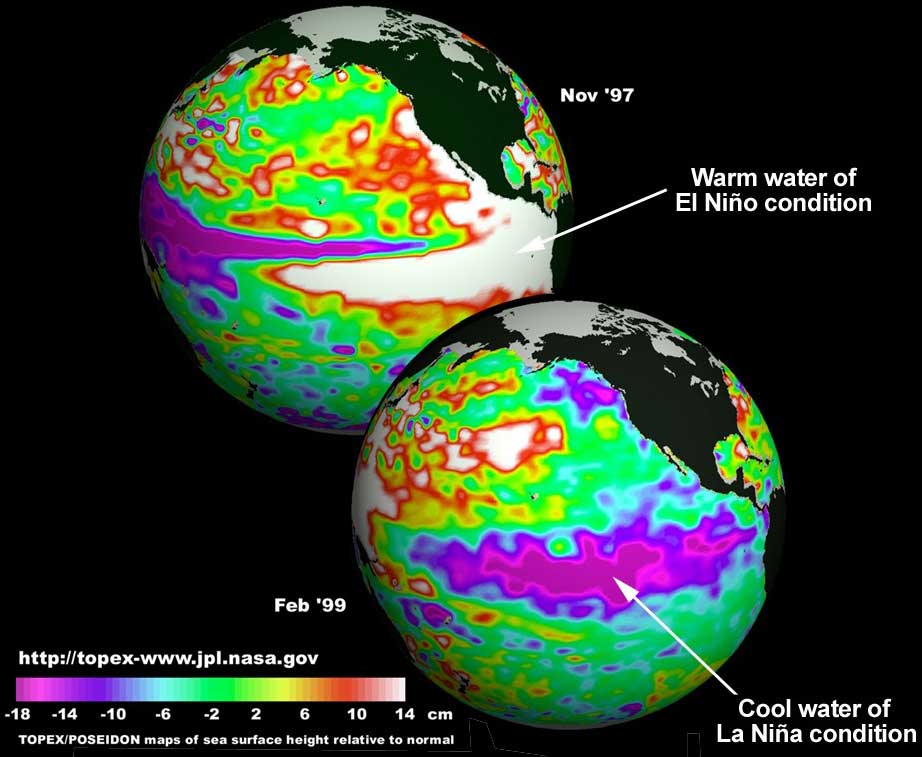

Slow fluctuations in sea surface temperature (SST) influence weather patterns around the globe. These fluctuations can be predicted, with some success, up to 6 months ahead from anomalies in the flow of surface currents.

Ocean current and temperature data are included in numerical models used to make seasonal predictions of the average weather you can expect over a large region - usually given as probabilities of temperature or rainfall being above or below the long-term average.

Seasonal forecasts for Europe are still experimental, and their reliability is relatively low. In the tropics, the link between SST patterns and seasonal weather trends is stronger, and seasonal forecasting is more successful, particularly in years with a strong El Niňo or La Niňa.

Satellite altimetry measurements of sea surface height anomalies (the deviation from the average sea surface height) allows us to monitor fluctuations in the tropical Pacific and detect the start of El Niňo events.