Supplement 2.12: Impact of Oil on Marine Flora and Fauna (2/3)

Bioaccumulation of hydrocarbons

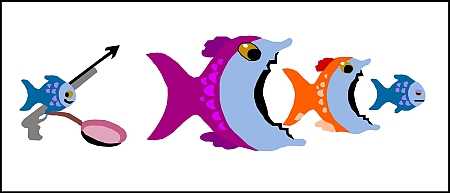

The incorporation of even minimal quantities of hydrocarbons in the tissue of a marine organism, through uptake of dissolved fractions across the gills or skin or direct ingestion of the pollutant, can affect its predators. If the pollutant is not broken down in the course of the organism's metabolic processes, it can become increasingly concentrated all the way along the food chain. This is the phenomenon of bioaccumulation of chemicals through the food chain until they reach considerably higher concentrations than those found in the water.

At every link in the food chain, organisms consume around 10 kg of matter from the level below to produce 1 kg of their own living matter. If a contaminant passes from one level to another without being broken down, its concentration in the living matter multiplies nearly ten times at each link in the chain! Organisms at the top of the chain can therefore be exposed to very high concentrations of a product which did not affect the organisms further down the chain and can be detrimental to their health.

Hydrocarbon bioaccumulation is often put forward as a major concern when an oil spill occurs. Fortunately however, many of the components of oil and petroleum products are biodegradable at some level of the food chain. Only the rarer, high molecular weight polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons tend to have a significant bioaccumulation potential as far as the highest levels of the food chain. Therefore bioaccumulation, if indeed it occurs, is generally of a sufficiently low level to be masked by other clearer phenomena in the incidence of an oil spill.

Tainting

An alteration of the taste and smell of seafood is one of the phenomena which can often be observed after an oil spill. Simple contact of hydrocarbons present in the water with the skin or gills can give marine animals a taste and smell considered unacceptable by consumers.

This particular effect is a serious issue in the management

of the consequences of an oil spill. Molluscs,

such as oysters and mussels, can absorb, through

filtering, considerable quantities of hydrocarbons

present in water.

For example, a 20 gramme

oyster filters some 48 litres of seawater per day. It

can multiply the concentration of a pollutant in its

tissues by 70,000 in relation to the surrounding environment.

Tainting can occur very quickly. It only takes a few hours to a few days of contact for the taste and smell to alter. Tainting can be tested through olfactory or organoleptic tests and can be quantified by analyses of the total hydrocarbon content in the organism's tissues. When transferred into hydrocarbon-free water, or when the pollution has ceased, the animals naturally purge themselves of the pollutant in a few weeks to a few months.

The tainting of crustaceans, fish and shellfish is common during an oil spill. The immediate response from authorities is to temporarily ban their collection or sale. It must then be determined whether the contaminated animals can be put on the market after decontamination or if they should be destroyed as a precaution. This question is an important issue in terms of the protection of consumers and the local economy, as well as the market reputation of the local seafood industry.